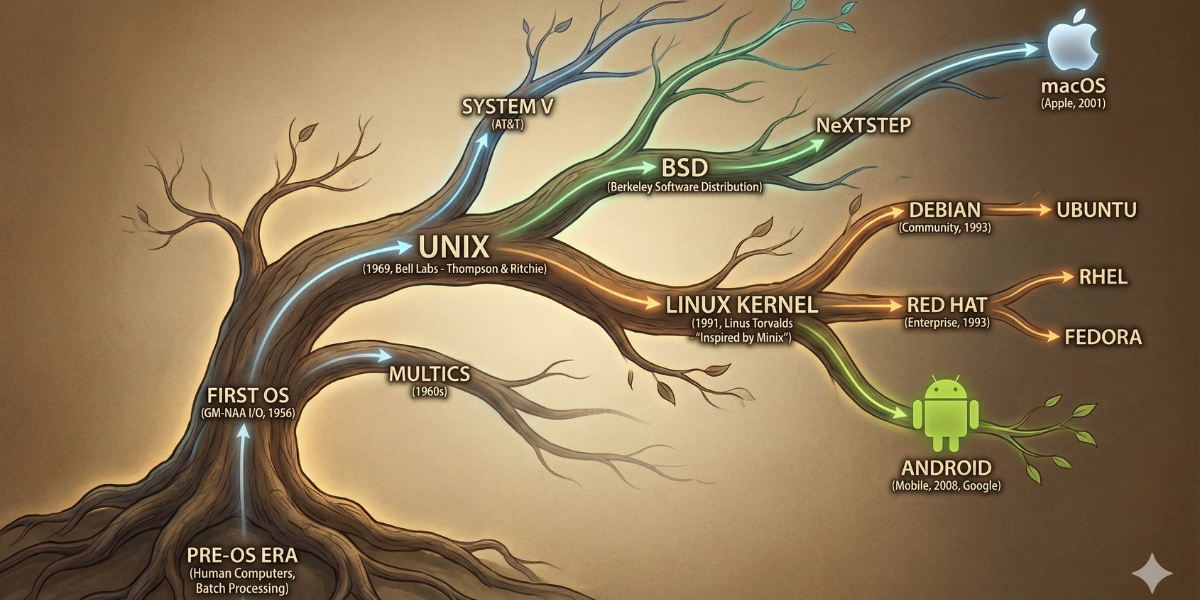

Hey everyone, in this article I have discussed about how Linux OS was invented. It is not possible for me to go back to time and see it with my own eyes because time machine still not invented. So I did some deep research on the Internet and found that you have to know the OS history from the begging. Did you ever get curious about why they were trying to create an Operating System? Well, do not worry my friend. Now you will know everything from the beginning. Lets go back to 1940s…

To understand the first operating system, we have to look at the problem it was trying to solve.

In the early days, computers were incredibly expensive (millions of dollars), and having them sit idle for even a few minutes while a human operator set things up was a massive financial loss.

Before the Operating System (1940s–Early 1950s):

Before operating systems existed, the “operating system” was a human being. This era is often called the “Open Shop” model.

How people used computers then:

Programmers did not write code in text editors. They wrote code on paper and translated it into machine code manually. On machines like the ENIAC, “programming” meant physically walking inside the computer and re-wiring cables (plugboards) or flipping toggle switches to set instructions. Later, programmers used machines to punch holes into stiff paper cards. A stack of these cards represented the program. Because the computer could only run one task at a time, programmers signed up for blocks of time (e.g., 2:00 PM – 3:00 PM) on a clipboard on the wall. When your time came, you walked into the computer room, mounted your magnetic tapes, loaded your deck of punch cards into the hopper, and pressed “Start.” If your program crashed, you had to look at lights on the console to debug it, then clear the machine for the next person. So the problem was the computer sat idle while humans walked around, loaded tapes, and set switches. This “setup time” wasted roughly 50% of the computer’s available time.

The First Operating System: GM-NAA I/O (1956):

Most computer historians consider the GM-NAA I/O to be the first true operating system. Created by General Motors (Research Division) for The IBM 704 mainframe to eliminate the “idle time” caused by humans.

General Motors didn’t want the computer to stop between jobs. They wrote a program (GM-NAA I/O) that stayed in the computer’s memory permanently.

Batch Processing: Instead of one programmer entering the room at a time, they handed their card decks to a professional operator.

The Batch: The operator combined 50 or 60 different jobs onto a single magnetic tape.

The Monitor: The GM-NAA I/O software would read the first job from the tape, run it, and when it finished, automatically load the next job without human intervention.

This was a “Batch Monitor,” not a complex OS like Windows or Linux today, but it was the first software designed to manage the hardware and run other software.

The Evolution: From Batch to Time-Sharing:

Once the concept of software managing hardware was proven, the evolution accelerated rapidly.

So what is Time-Sharing in computers?

Time sharing is a method that allows many users to share a single powerful computer simultaneously.

Here is a breakdown of how it works, why it was invented, and the mechanism behind it.

Imagine a Chess Grandmaster playing against 50 opponents at the same time. The Grandmaster walks to Board 1, spends 5 seconds making a move –> move to Board 2, spend 5 seconds making a move –> continue down the line..

By the time the Grandmaster returns to Board 1, the opponent has had plenty of time to think and move. To the opponent at Board 1, it feels like they are playing a continuous game, even though the Grandmaster was gone for several minutes.

In computing:

- The Grandmaster is the CPU (Processor).

- The Opponents are the Users/Programs.

- The 5 Seconds is the “Time Slice.”

How It Works Technically:

Time sharing relies on a specific mechanism called Round Robin Scheduling and Context Switching.

The operating system assigns a tiny specific amount of time (e.g., 20 milliseconds) to User A –> The CPU runs User A’s program –> When the 20ms is up, a hardware timer sends a signal (an interrupt) to stop the CPU –> The OS pauses User A, saves exactly where they were (saving the “state”), and loads User B’s program –> This cycle repeats for all users in a loop.

Because the CPU is electronic and moves at the speed of light, it can cycle through 100 users in the blink of an eye.

Before time sharing, computers used Batch Processing.

Batch (The Old Way): You handed a stack of punch cards to an operator. The computer ran your program from start to finish. You waited hours for the printout. You had zero interaction with the machine while it ran.

Time Sharing (The New Way): You sat at a terminal (keyboard/screen). You typed a command, and the computer responded immediately.

The Impact:

Interactivity: It allowed programmers to debug code in real-time.

Efficiency: While User A was typing (which takes “forever” in computer time), the CPU wasn’t idle; it was processing User B’s calculation.

Cost: It made computing affordable. A university couldn’t buy a mainframe for every student, but they could buy one mainframe and 30 cheap terminals.

Famous Time-Sharing Systems: CTSS (Compatible Time-Sharing System), Developed at MIT in 1961, this is generally cited as the first true time-sharing system.

Time Sharing Today (Multitasking)

We generally don’t use the term “Time Sharing” anymore because computers are now cheap enough that we have our own. However, the technology evolved into Multitasking.

Even on your personal laptop or phone, “Time Sharing” logic is still happening:

- Your Spotify music, your browser tabs, and your background system updates are all “users” fighting for the CPU’s attention.

- The OS slices time between them so your music doesn’t skip while you browse the web.

The Multics project (1960s)

The history of Unix is one of the most significant narratives in computing. It is the story of how a “failed” project at Bell Labs evolved into the backbone of the modern internet, supercomputers, and smartphones.

The Pre-History: The Fall of Multics (1960s)

In the mid-1960s, a consortium including MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), General Electric, and AT&T‘s Bell Labs worked on a project called Multics (Multiplexed Information and Computing Service).

The goal was to create an operating system that could support hundreds of simultaneous users, offering high availability and security—essentially a “computing utility” like a power plant. But the reality is Multics was overly complex, slow, and bloated. It struggled to deliver on its promises. In 1969, Bell Labs, frustrated by the lack of progress and high costs, pulled out of the project.

The Birth of Unix (1969)

Among the Bell Labs researchers who left Multics were Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie. They had become accustomed to the interactive environment of Multics and didn’t want to return to batch processing.

The “Space Travel” Game: Thompson found an unused DEC PDP-7 minicomputer. He initially wanted to write a game called Space Travel, but he needed an operating system to run it efficiently.

Uniplexed Information and Computing Service: In August 1969, Ken Thompson, working closely with Ritchie, Rudd Canaday, and others, wrote a basic OS in assembly language.

Unix Naming: It was originally jokingly named UNICS (a pun on Multics, suggesting “Emasculated” or “Single” service) by colleague Peter Neumann. eventually, the spelling settled on Unix.

Assembly Language: Assembly language is a low-level programming language that is very close to the computer’s actual hardware instructions. It’s basically a human-readable version of machine code. Unlike high-level languages, assembly works directly with CPU registers and memory locations.

The C Language Revolution (1972–1973)

This is arguably the most critical moment in operating system history.

Early Unix was written in Assembly, meaning it was tied to specific hardware (the PDP-7 and later PDP-11). If you bought a different computer, you had to rewrite the OS. Dennis Ritchie developed a new high-level programming language called C. In 1973, Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie rewrote the Unix kernel in C. This made Unix portable. For the first time, an OS could be moved to a completely different computer architecture with minimal changes.

The Great Split: System V vs. BSD (Late 1970s–1980s)

Due to a 1956 antitrust decree, AT&T (the owner of Bell Labs) was forbidden from selling software commercially. Consequently, they licensed Unix source code to universities for a nominal fee. This led to two major branches of development:

The Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD): The University of California, Berkeley, received the source code and began modifying it. Graduate student Bill Joy (who later co-founded Sun Microsystems) was a key figure. BSD added TCP/IP networking (foundation of the internet), the vi editor, and the C shell (csh).

AT&T System V: In 1982, the US government broke up the Bell System (AT&T). Relieved of the antitrust restriction, AT&T quickly commercialized Unix. They released System V (SysV) in 1983, intending it to be the industry standard.

The Unix Wars (1980s–Early 1990s)

A “war” erupted between vendors trying to lock customers into their specific version of Unix. The Players were Sun Microsystems: Used a version based on BSD (SunOS/Solaris), HP: HP-UX (based on System V), IBM: AIX (based on System V). So code written for one Unix often wouldn’t run on another. This fragmentation frustrated developers and customers.

Standardization (POSIX): To fix this, the IEEE developed POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface) in 1988. This defined a standard API so software could be compatible across different Unix variants.

The Rise of Open Source: GNU and Linux (1990s)

While corporations fought over Unix, a quiet revolution was happening in the background.

The GNU Project (1983): Richard Stallman launched the GNU project with the goal of creating a completely free, Unix-like operating system. By the early 90s, they had created nearly everything (compilers, editors, shells) except the kernel.

Minix: Andrew Tanenbaum created a small educational Unix clone called Minix. It was useful for teaching but restricted in license.

Linus Torvalds (1991): A Finnish student named Linus Torvalds wanted a free OS that took advantage of the 386 processor. He wrote a kernel as a hobby project.

GNU + Linux: Developers quickly realized that Torvalds’ kernel (Linux) filled the missing piece of the GNU project. The combination became the open-source OS we know today.

Linus Torvalds and Linux

This is one of the most famous origin stories in computer science. It is important to clarify a common misconception right away: Linux was not based on the Minix code. Linux was written from scratch on a Minix system, inspired by Minix’s design, but it did not use Minix’s source code.

Andrew Tanenbaum and MINIX (1987): In the late 1980s, the educational landscape for operating systems was bleak. The standard OS for study was Unix, but AT&T had commercialized it, making the source code expensive and legally restricted. Andrew Tanenbaum, a professor in Amsterdam, wanted his students to be able to tinker with an OS without legal trouble. He wrote MINIX (Mini-Unix). It was a “microkernel”—highly modular and designed for education, not performance. To keep the code simple for students, Tanenbaum refused to add complex features. He also designed it for older 16-bit chips (Intel 8088), ignoring the powerful new 32-bit chips emerging on the market.

The Motivation: The 386 Chip (1991)

In January 1991, Linus Torvalds, a 21-year-old student at the University of Helsinki, bought a new PC. It was a clone equipped with the Intel 386 processor. This chip was special, it was 32-bit and had hardware support for multitasking (switching between programs).

Linus installed MINIX on his new PC, but he was immediately frustrated. He wanted to connect to the university’s powerful computers to read email and newsgroups. The terminal software in MINIX was clunky. MINIX was written for older chips. It didn’t utilize the 386’s advanced memory management or task-switching features.

The Creation: From “Project” to “Kernel”

Linus didn’t set out to write an operating system. He set out to learn how his new 386 processor worked.

Step 1: The Task Switcher (Spring 1991)

- Linus wrote a simple program in Assembly language to test the 386’s task-switching.

- It had two processes: one that printed AAAA… and one that printed BBBB…

- A timer would switch between them.

- Significance: This was the primitive “scheduler”—the heart of an OS.

Step 2: The Terminal Emulator He expanded his AAAA/BBBB program into a terminal emulator.

- Process A read from the keyboard and sent to the modem.

- Process B read from the modem and sent to the screen.

- Because he was writing it at the hardware level (bare metal), it was faster and smoother than the software running on Minix.

Step 3: The “Feature Creep” (Summer 1991)

- Linus realized he needed to download files from the university server to his PC.

- To save a file, he needed a Disk Driver. He wrote one.

- To organize the files, he needed a File System. He wrote one (compatible with Minix’s file system).

- Once he had task switching, a disk driver, and a file system, he realized: “I have essentially written an operating system.”

Step 4: The Bash Shell (The Turning Point)

The system was useless if it couldn’t run programs. Linus struggled to port the Bash shell (the command line interface from the GNU project) to his new kernel. When he finally got Bash to run and display a prompt (#), it was the moment the project became a real OS.

The Announcement

On August 25, 1991, Linus posted a now-legendary message to the Usenet newsgroup comp.os.minix

“Hello everybody out there using minix – I’m doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won’t be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones…”

How it was Named: “Freax” vs. “Linux”

Linus never intended to name the OS after himself. He thought that was egocentric. He wanted to call it Freax [Free + Freak + X (as in Unix)].

Ari Lemmke’s Intervention: Linus needed a place to upload his files so others could download them. Ari Lemmke, a volunteer administrator for the FTP server at the Helsinki University of Technology, offered him space. Ari disliked the name “Freax.” Without asking Linus, he named the directory on the server pub/OS/Linux (Linus’s Minix). Linus initially resisted, but eventually admitted that “Linux” was a better name than “Freax,” and he let it stick.

The Philosophical Clash (1992): The relationship between Minix and Linux culminated in a famous debate. Andrew Tanenbaum (creator of Minix) posted a critique titled “LINUX is obsolete.” Tanenbaum argued that Linux used a “Monolithic Kernel” (all drivers in one big chunk), which was an old-fashioned design compared to Minix’s “Microkernel” (drivers separated for stability). Linus argued that Microkernels were theoretically nice but practical nightmares. He preferred the raw performance and simplicity of the Monolithic design.

History ultimately sided with Linus on practical adoption.

The Linux Operating System we use today

Debian: The Community Standard (1993)

The “Mother” of distributions. In the early days of Linux (1991–1992), you had to compile the kernel yourself. Early attempts to bundle Linux into an easy-to-install package (a “distribution”) were buggy and poorly maintained. Ian Murdock, a student at Purdue University, was frustrated with the existing “SLS” distribution. In 1993 he announced the Debian Project. The name was a combination of his girlfriend’s name (Debra) and his own (Ian). Unlike other systems that were rushing to make money, Debian was founded on the Debian Social Contract. It promised to remain 100% free (open source) and effectively govern itself by community voting, not a corporate CEO.

Debian invented apt (Advanced Package Tool), solving the nightmare of installing software dependencies. It became the foundation for Ubuntu (2004), which took Debian’s stable code and polished it for non-technical users. Today, Debian is the bedrock for roughly 60% of all active Linux distributions.

Red Hat (RHEL): The Enterprise Giant (1993–2002)

While Debian focused on community, Bob Young and Marc Ewing saw a business opportunity. They released Red Hat Linux, which became popular for its ease of use (RPM package manager).

The “guy in the red hat” primarily refers to Marc Ewing, co-founder of Red Hat, who wore his grandfather’s red Cornell lacrosse cap while studying at Carnegie Mellon. His reputation for being helpful led to the phrase “if you need help, look for the guy in the red hat,” which inspired the company’s name and logo.

In 2000s, Red Hat realized they couldn’t support a rapidly changing “free” version for big banks and governments who needed stability for 10 years at a time.

(2002/2003) They killed the original “Red Hat Linux” and split it into two:

Fedora: The “testing ground.” Free, fast-moving, and community-driven. New features are tested here first.

RHEL (Red Hat Enterprise Linux): The “commercial product.” Once code is stable in Fedora, it is moved to RHEL. It changes very slowly and comes with expensive support contracts.

This model made Red Hat the first billion-dollar open-source company, eventually leading to their acquisition by IBM for $34 billion in 2019.

macOS (1996–2001):

In the mid-90s, Apple was on the brink of bankruptcy. Their operating system (Mac OS 9) was archaic—it crashed constantly and lacked modern multitasking. Apple tried to write a new OS (Copland) and failed. They looked outside to buy one. They considered BeOS but ultimately bought NeXT, the company Steve Jobs founded after being fired from Apple. Steve Jobs brought with him the NeXTSTEP operating system. It was built on the Mach Kernel and BSD Unix (the University of California branch we discussed earlier). Apple took this Unix core (called Darwin) and built a polished graphical interface (Aqua) on top of it. In 2001, Mac OS X (Cheetah) was released.

It was the first time a certified Unix system became a mass-market consumer product. Under the hood, your MacBook is a close cousin to the servers running the internet.

Android: Linux in Your Pocket (2003–2008)

Android did not start at Google. It started as a start-up Android Inc. in 2003, led by Andy Rubin. They wanted to build an advanced operating system for digital cameras. However, they realized the camera market was shrinking and the phone market was exploding. In 2005, Google acquired Android Inc. They knew they needed to enter the mobile space but didn’t want to build a kernel from scratch.

Why Android Team choose Linux?

- Was already stable and handled memory well.

- Supported a vast array of hardware drivers.

- Was free to modify.

The Linux Kernel was the perfect fit.

Android uses the Linux kernel, but it does not use the standard GNU tools (like the Bash shell or X window system) found in Debian or Red Hat. Instead, it runs a virtual machine (originally Dalvik, now ART) on top of the Linux kernel to run Java/Kotlin apps.

In 2008, the HTC Dream (G1) was the first Android phone. Because it was open source (AOSP), manufacturers like Samsung and Motorola could use it for free, allowing it to rapidly capture 70%+ of the global market.

The Family Reunion

Unix (1969): The Grandfather.

BSD Branch: Led to macOS.

Linux (1991): The Son (Unix-like, but new code).

Debian (1993): The “Community” grandchild (led to Ubuntu, Kali).

Red Hat (1994): The “Corporate” grandchild (led to RHEL, Fedora, CentOS).

Android (2008): The “Rebel” grandchild (Uses the Linux kernel, but completely different DNA above it).